Why Your LLC or S-Corp Is Quietly Killing Your Legacy (History Proves It)

- Dewayne Williams

- Aug 14, 2025

- 6 min read

Why start with history?

Because structure isn’t about hype; it’s about what has endured. If you’re aiming for generational wealth, follow what has stood the test of time—not what’s trendy this decade.

A quick timeline that actually matters

C-Corporation (the original “separate person”)

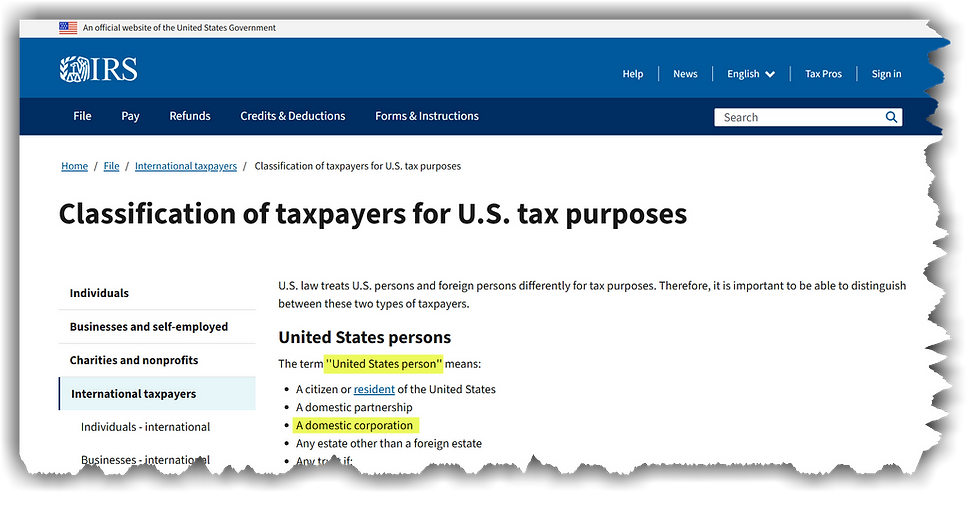

In U.S. law and tax, a C-Corp is its own legal and taxpaying person.

It earns income, files its own return, pays its own taxes, and can retain earnings.

Why this matters: Separation. Institutional credibility. The ability to build corporate history, corporate credit, and keep profits in the company for scale.

S-Corporation (a tax label, not an entity)

In 1958, Congress added Subchapter S so certain closely-held corporations could pass income/losses through to owners’ personal returns—avoiding classic double tax.

You elect this with Form 2553.

You do not register an “S-Corp” at the Secretary of State.

Why this matters: S-Corp is a tax election layered on top of an entity.

It doesn’t create separation by itself

It routes profits to your 1040.

LLC (a very new invention, historically speaking)

First U.S. LLC statute: Wyoming, 1977.

The last state to adopt an LLC statute was Hawaiʻi, effective Jan 1, 1997.

Translation: LLCs are only a few decades old.

Why this matters: LLCs are modern and flexible—but new compared to the corporate form. New isn’t “bad,” but be crystal clear about what it does and doesn’t do for separation and legacy.

History in action: Heinz → Berkshire → Buffett

Heinz Ketchup first hit U.S. shelves in 1876—149 years ago. That’s staying power.

Today the brand lives inside The Kraft Heinz Company, formed by the 2015 merger of Heinz and Kraft—where Berkshire Hathaway has been a major shareholder (roughly ~27% in recent years).

Point: Enduring companies are built on corporate foundations. If the goal is generational wealth, study the structures used by institutions that outlast people.

The real S-Corp conversation (without the sales pitch)

What people mean when they say “elect S-Corp to save taxes” is simple:

You pay yourself W-2 “reasonable compensation.”

Profits above that wage pass through to you and skip payroll taxes (Social Security/Medicare).

Those profits still land on your Form 1040 and are fully subject to federal income tax. The S-election didn’t erase income tax—it only affected payroll tax.

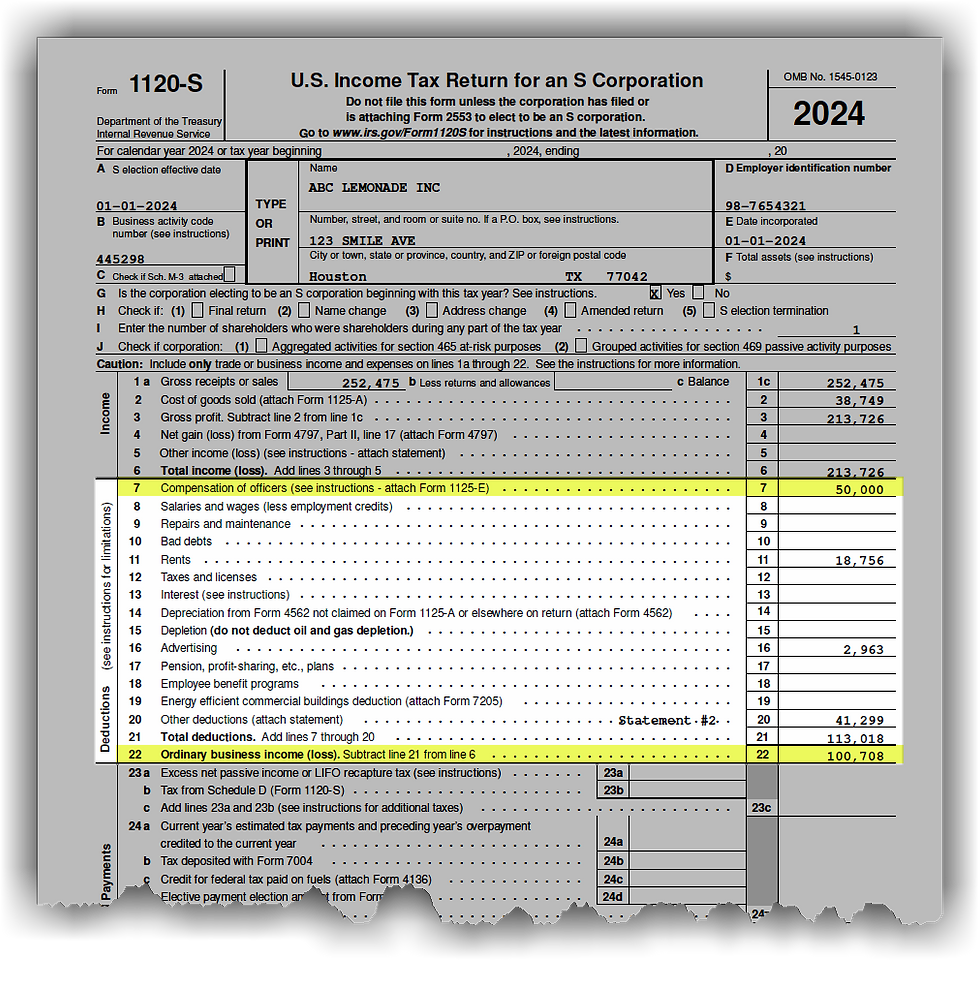

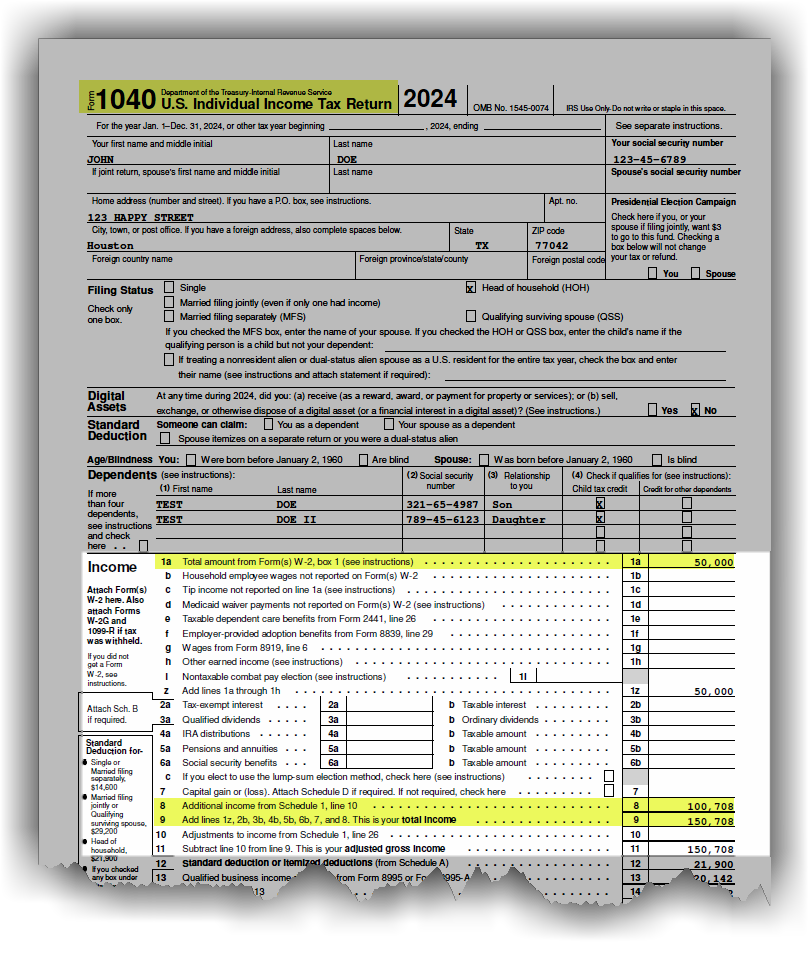

Step 1 (1120-S): S-Corp pays you $50,000 (W-2) and shows $100,708 profit.

The company paid you $50,000 in W-2 wages (called Officer Compensation) and still had $100,708 left as Ordinary Business Income.

That $100,708 doesn’t stay in the company for tax purposes—it passes through to you personally on a K-1 and will show up on my personal tax return.

Why this matters:The S-Corp creates two streams for you: a salary (W-2) and pass-through profit (the K-1 amount).

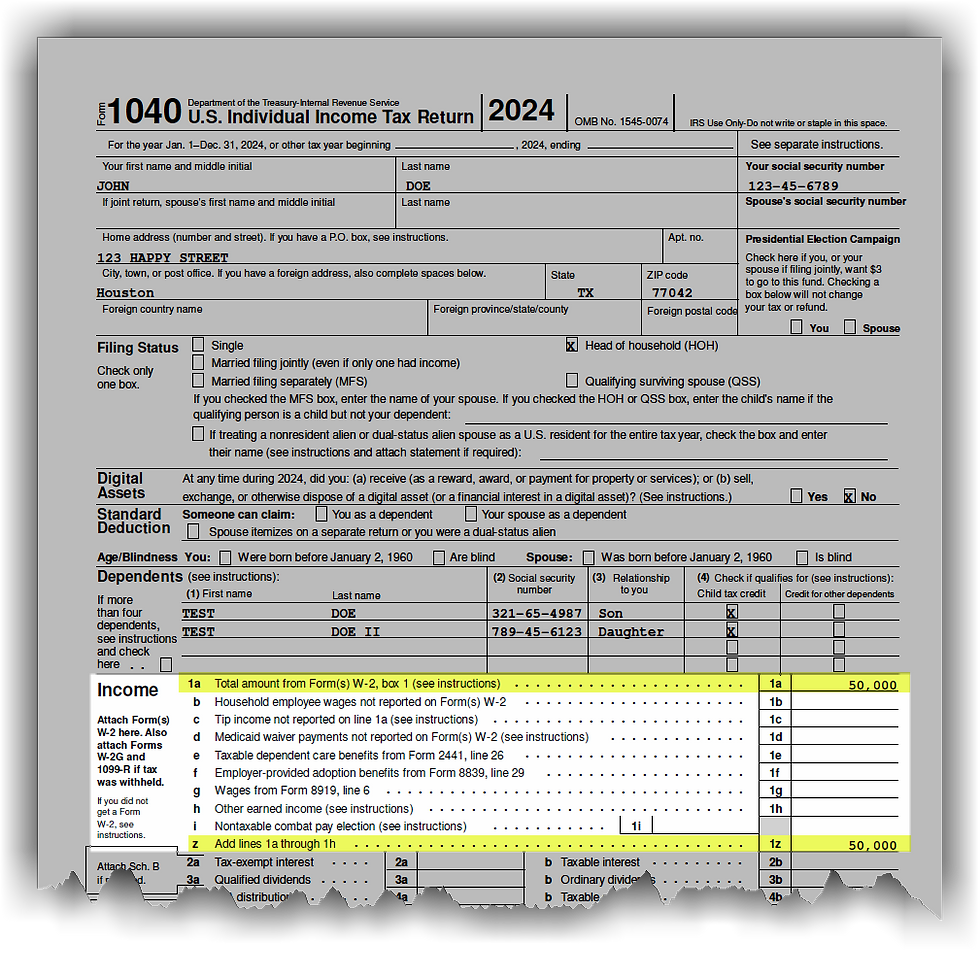

Step 2 (1040): Your $50,000 appears as W-2 wages (payroll taxes apply).

The $50,000 shows up on Line 1 as W-2 wages you paid yourself from the S-Corp.

This part is subject to payroll taxes (Social Security/Medicare) because it’s a paycheck.

Why this matters:The salary is taxed like any employee’s wages—payroll taxes apply here.

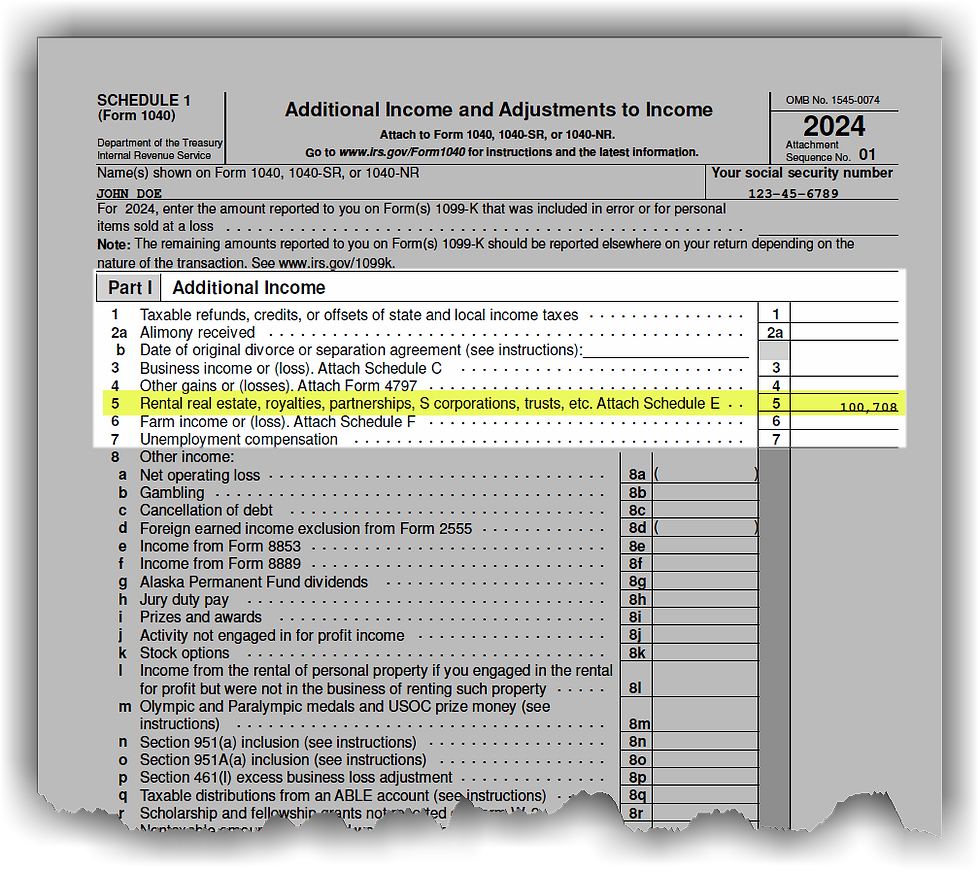

Step 3 (Schedule 1): The $100,708 profit passes through to your personal return (no payroll tax, but income tax still due).

The $100,708 of Ordinary Business Income passes through from the S-Corp and is reported as Additional Income on Schedule 1 (flowing onto my 1040).

Key point: This skips payroll taxes, but it’s still fully subject to federal income tax—and now it lives on your return.

Why this matters:Passing profit to your 1040 means You're responsible for the income tax—and lenders will underwrite you, not the company.

Step 4 (1040 total): Your personal return now shows $50,000 + $100,708.

You’ve got $50,000 in wages plus $100,708 in pass-through profit from the S-Corp.

Translation:The S-Corp didn’t “erase taxes”—it only avoided payroll tax on the $100,708.

You still owe income tax on both amounts, and because the profit sits on your personal return, You're the one lenders and underwriters look at.

That’s why they ask for personal guarantees—you look like the business.

Why this matters:The moment profit hits your 1040, you’ve undone the spirit of separation financially.

The mindset trap: structuring around taxes = thinking like an employee

From your first paycheck, taxes were taken out automatically. That conditions most new owners to chase tax treatment instead of liability treatment.

But when you formed your company, the state and the IRS didn’t ask, “How much tax do you want to pay?” They asked, “How do you want to be treated?” (for liability and classification). Elections like 2553 (S-Corp) or 8832 (entity classification) tell the IRS how to tax what you already formed—they do not build separation.

Translation: If you structure primarily to “save taxes,” you’re still playing wage-earner games. Owners design for separation first, then optimize taxes inside that structure.

🔎 The missing connection most people never see

1) Legal liability vs. financial liability are two different animals

Legal liability = whether someone can sue you personally for the company’s debts/obligations. The corporate veil can block that unless you pierce it (commingling, personal guarantees, fraud, ignoring formalities).

Financial liability = who is actually responsible for repaying money or taxes. If profits show up on your 1040, you are responsible for the tax bill and for proving that income to lenders/underwriters.

2) S-Corp’s pass-through forces personal responsibility

When S-Corp income hits your personal return:

The IRS holds you responsible for the tax—not the company.

Lenders view you as the source of repayment—not the business.

Most credit/loans/contracts will require your personal guarantee.

➡️ In effect, the moment all profits are forced through to your personal tax return, you’ve undone the spirit of separation financially—even if the entity is technically separate at the state level.

3) C-Corp = the only true separation

A properly run C-Corp:

Files its own federal return.

Pays its own tax bill.

Can retain earnings and build capital without pushing them to your 1040.

Keeps profits, liabilities, and creditworthiness in the company’s name—no automatic personal responsibility unless you choose to guarantee something.

4) LLC and S-Corp share the same federal flaw

LLCs are recognized at the state level. Once you get a federal EIN and transact in U.S. dollars, you’re in federal tax jurisdiction, and the IRS classifies the LLC for tax.

Single-member LLC → taxed like a sole prop.

Multi-member LLC → taxed like a partnership.

LLC taxed as S-Corp → pass-through right back to your personal return.

In all of these pass-through setups, business income lives on your personal return, tying your financial life directly to the company’s fortunes.

If your goal is generational wealth, let history lead you

Heinz didn’t become a 149-year-old staple by optimizing a payroll tax. It scaled inside corporate structures, then merged into a larger corporate platform with institutional investors.

So ask yourself:

Do you want a structure that puts profits on your 1040 (keeping you personally on the hook)?

Or a structure that stands separate from you, builds corporate credit, and can be managed by a team you hire?

My stance, plain

S-Corp = tax election. “Savings” = mostly payroll taxes. Profits still hit your 1040.

LLC = modern and flexible, but by default passes income to you and often keeps the founder at the center.

C-Corp = separation, retained earnings, and an institutional posture that supports legacy.

References

IRS — Forming a corporation (C-corp is a separate taxpaying entity):

IRS — About Form 2553 (S-corp election):

IRS — Form 2553 (PDF):

IRS — Instructions for Form 2553:

Congressional Research Service — A Brief Overview of Business Types and Their Tax Treatment (S-corp as a tax election under Subchapter S):

U.S. House Hearing (historical note on 1958 creation of Subchapter S):

S Corporation Association — History of Subchapter S:

Wyoming LLC history (first U.S. LLC statute, 1977):

Additional Wyoming source on 1977 act:

Hawai‘i Revised Statutes — Chapter 428 (LLC Act):

Hawai‘i — 1997 Session Law (Act 4) re: LLCs:

(Background note that Hawai‘i was last to adopt LLC statute):

Heinz — “Our Story” (ketchup introduced in 1876):

Kraft Heinz press release (2015 merger; Berkshire Hathaway + 3G Capital investment):

SEC archive of the same press release:

Time coverage of Kraft–Heinz merger (context):

Comments